ISFANDIYOR NAZAR: "NATIONAL SELF-AWARENESS" AFTER LOIK, KANOAT, BOZOR, AND GULRUKHSOR HAS BECOME TRIBAL LIMITATION

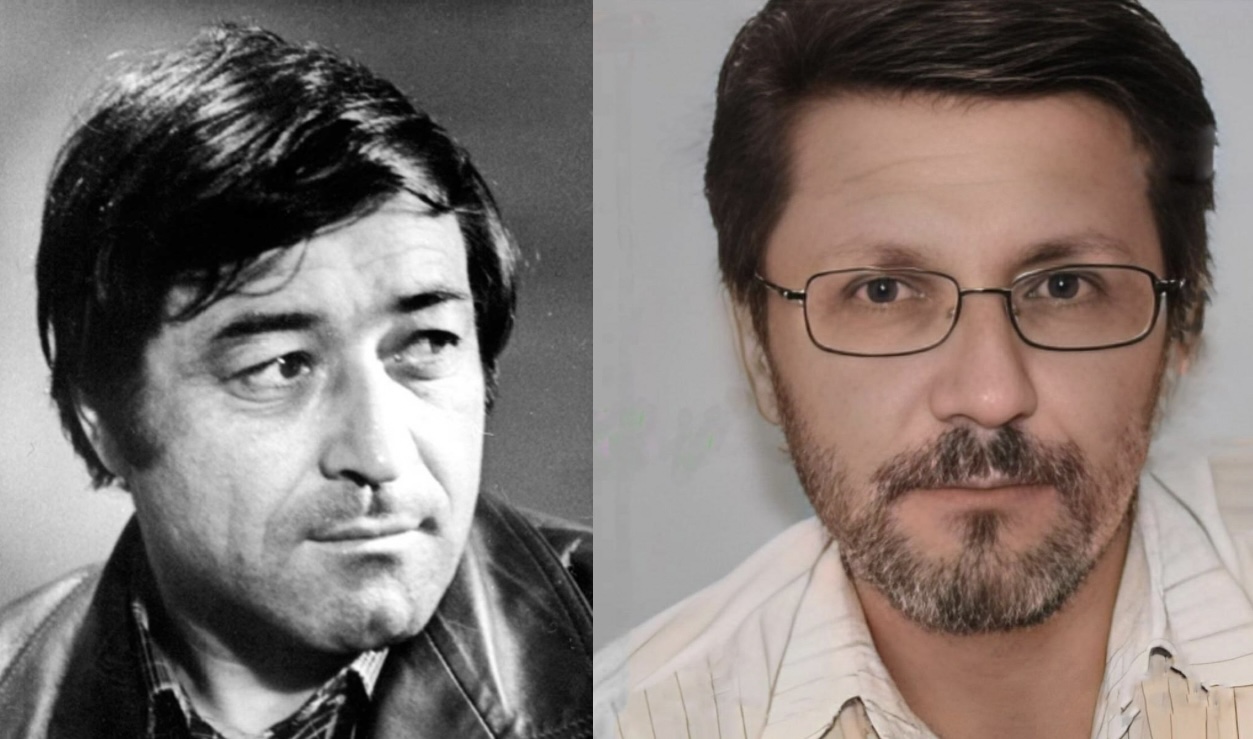

"Oiina" planned to publish an interview on May 20, the birthday of the great contemporary Tajik poet Loik Sherali, on the topic of poetry, poets, and Loik Sherali's place in modern Tajik literature, with Isfandiyor Nazar, another prominent national poet whose poetry is filled with the pain of the Tajik people. However, for various reasons, we were unable to publish this interview on Loik Sherali's birthday, who, had fate been kinder to him, would have celebrated his 82nd birthday.

Nevertheless, the creative team believes that it is never too late to remind the nation of a person who pointed the way to its essence and existence. Therefore, we publish this interview with deep apologies to the spirit of Loik Sherali and our esteemed readers.

"Oiina": — Loik Sherali is remembered as a poet who broke stereotypes and brought poetry out of the confines of established canons. Did this breakthrough happen, and in what form?

I. Nazar: — Before answering your question, I would like to emphasize that it is better not to simply refer to Loik Sherali as "Loik Sherali" and not to use the word "teacher," which has now been attached to everyone's name and has lost its value, before the name of a poet like Loik Sherali. Why? Because calling a young and inexperienced poet a teacher compared to a great poet is, in fact, a devaluation of both the title and poetry and the status of the poet himself. I have suggested using the term "great teacher" to describe outstanding national poets. Although I see that even this term has started to be applied to poets with mediocre poetry.

Therefore, poets such as Rudaki, the leader of the caravan, Hakim Ferdowsi, Nosir Khisrav Qubodiyoni, Domullo Ayni, the great Lohuti, epic poet Mu’min Qanoat, and the sun of the last hundred years of Tajik poetry, Loik Sherali, I consider, name, and recognize as "great teachers."

Now to your question: after the passionate, love, mystical, and patriotic poetry of the great teacher Lohuti, Tajik poetry indeed turned into a slogan. But this does not mean that Tajik poetry died for a while, no! Poetry was alive, but it was pushed into the framework of dry ideology and the "patriotism" program. Poetry lost its main essence and began to glorify canals, cotton fields, and women picking cotton.

Let me give you an example: in our village, Usto Rahim, playing the daf, sang the ghazal "The Canal Has Come" by Loik Sherali until the end of his life:

"O wind, convey to our friends that the canal has come!"

The poetry of that time lost its ancient foundation, lost its decorations and imagery, turning into a dry form.

Poets were instructed to go to the "Kazakh steppes" and create works about the people who were greening those steppes. Writers were ordered to write about the irrigation of the Vakhsh Valley.

Of course, talented poets and writers even created good works from such artificial themes for their readers, but, be that as it may, it is difficult to expect long life from poetry and prose written by party directives. The exceptions are historical works such as chronicles, translations, and similar ones created by orders of emirs and ministers.

It should be noted that not all poetry of that time was dry and soulless, but in general, it can be evaluated equally. For example, if you read the complete collection of poems by Suhaily Javharizoda — the son of the great poet Javhariya Istaravshani, published during Soviet times, you may not find a single memorable line. In any case, I did not find any.

The breakthrough and rescue of Persian-Tajik poetry from these artificial frameworks, although not directly achieved by the great teacher Loik Sherali himself, were solidified and completed in his outstanding poetry.

Yes, before the great teacher Loik, there was a poet in the literature of that time like Aminjon Shukuri. Aminjon Shukuri, as much as his ability and talent allowed, paved a new path, and his poetry influenced the young poets who came after him.

Then came the young Loik Sherali, and with his arrival, the image and influence of other poets quickly faded.

The poetry of this poet was fresh, bringing the breath of classical poetry in a living language, with many new words that were not present in the poetry of others. The breakthrough of the great teacher Loik arose from his own rebellious spirit, meaning he created it naturally, without intending to, and without being guided, as if he was born to fulfill this mission. And this happened a thousand years after the great teacher Rudaki!

"Oiina": — They say that before Loik, no poem by a young poet was published without significant editing, but many "exceptions" were made for Loik. For example, the requirement for joining the Writers' Union was to have at least one collection of poems or prose published, but Loik Sherali was accepted into the union with just three poems. I would like to know your opinion on the level of weight, meaning, content, and poetic insight of Loik at that time, that led to his recognition.

I. Nazar: — In my opinion, "editing" did not concern political views but was focused on improving the quality of the poetry and prose itself. After all, it was difficult to catch a whiff of rebellion in the poetry of that time — a rebellion against the Soviet system. Elements of rebellion were more common in prose. In any case, elements of rebellion began to appear in poetry and prose after the 1960s.

"Exceptions" were made not only for the young Loik. These exceptions were also applied to poets like Qutbi Sarkash and others. And these exceptions were made not because of the weakness of their poems but rather because of their rebelliousness, defiance, and rule-breaking.

Great teachers like Tursunzade, Rahimzade, Mirshakar, and Qanoat tried to cover up the "sins" of this generation so that they would not be crushed by the system.

These "exceptions" were made because of their talent, which was supposed to fill the void and elevate the new Soviet Tajik literature to its peak.

In fact, this generation did not betray the faith and conviction of their teachers, and they managed to raise Tajik poetry and prose to the summit and gain eternal pride for themselves.

The acceptance of such a young poet as Loik, whose fame had swept through the literary and social circles like a storm, was a "violation of the law" by the great teacher Tursunzade, contrary to the rules of the Writers' Union. After young Loik read his poem "To My Mother," he was nominated for membership in the Writers' Union.

In fact, the poem "To My Mother" at that time (and even now!) was more valuable than hundreds of collections of poems; it was a new poem, with deep meaning and a tender soul! The recognition of a true gem played its role. Perhaps gems can be found everywhere, but a true gemologist is hard to find…

“Oiina”:— During Loik’s era, the Iranian poet Alireza Kazva criticized the poetry of Tajik poets, and his criticism sparked many remarks. Loik Sherali partially acknowledged the validity of Kazva’s remarks regarding some Tajik poets, but in some cases, he considered Kazva’s criticism unprofessional and biased. I would like to know your opinion on this matter, as well as about the state and content of modern Tajik poetry…

I. Nazar: — In one sentence, I will say: the collection that Alireza Kazva compiled and published was absolutely accurate in its assessment, as he had access only to those poems and poets! In that collection, there are people referred to as “poets,” about whom not only Kazva but even the literary community of Tajikistan had heard and read for the first time…

However, Kazva fairly evaluated the poetry of such true poets as the great teacher Loik and his contemporaries and comrades.

It should be noted that the choice of themes in Tajik poetry is very good, but their development in the poems is another matter.

Of course, our modern poetry has made significant progress. Its authors are familiar with Persian script, and even if they are not, they have read many poems by their compatriots written in this script and have benefited from them. But what holds this poetry in place is the repetition of themes, clichéd love lyrics, frequent imitation of compatriot poets, and, worse still, the lack of poems that would prompt the reader to reflect and explore!

Poetry is not just for music and singers; it has other great missions as well. One of the missions of poetry is to make the reader think. Another weakness of our poetry is that it lacks social issues and public resonance. Our poets write poems about the deaths of Muslims in Miami, Palestine, Syria, or Iraq, but they lack the courage to express the problems of their own country.

And if they do write, they store them “for later” in their archives…

“Oiina”: — Why are Mu’min Qanoat, Loik Sherali, Bozor Sobir, and a few other poets remembered as the ones who revived national consciousness? How, in your opinion, does the national consciousness that Loik spoke of differ from the one described by his contemporaries or today’s poets?

I. Nazar: — To be a bearer of national consciousness, whether a poet, writer, teacher, or leader, one must have a deep knowledge of the capabilities and wealth of their native language. The level of knowledge of the language and history of our writers can be determined from their works.

The great figures you mentioned were not just poets; they were keepers of the great and infinite treasure of their native language, connoisseurs, and thinkers. They knew how to compare global issues with the issues of their country, thought about and influenced them, and this was reflected in their poetry.

The social problems these poets faced were more serious than the current problems of our society. They stood against a supposedly invincible empire, against the security of a country that monitored your every breath!

They also knew that they were risking their lives, but they were called to it, and their voices naturally grew louder. That is why they took the discussion of the native language out of secret meetings and table talks, onto the pages of newspapers, and ignited its fire in their poetry.

In the issue of the native language, the undeniable standard-bearer and leader among the fighting poets was the great teacher Loik! Then came the question of saving historical cities and great cultural and historical figures from the encroachment of Pan-Turkism. In this matter, too, the great teacher Qanoat and his contemporaries Loik, Bozor, Gulrukhsor, and Gulnazar wrote such poems that since then, no one has been able to say anything new or add anything to these themes.

If we speak of Samarkand and Bukhara, if we talk about the problems of the language’s name or its state and status, if we mention the great Avicenna, Nizami, Rumi, or… all of this has already been said by them! They were able to partially solve the language issues with their courage, but we have driven them into an even deeper hole, and our poets, unlike them, avoided the struggle and rejected the true name of the language in its homeland!

The problems of Samarkand and Bukhara, the issues of historical figures, and the invasion and encroachment by outsiders still continue; we cannot say anything new and have made ourselves more pathetic than we are.

Our modern poetry does not look to open horizons; like a silkworm, it continues to enclose itself in the cocoon of its own words, making them more and more limited, limiting its language and its history. A poet who seeks titles, wants to please officials, fears the wrath of the authorities… in short, wants to be harmless and unnoticed, cannot be called a poet.

A poet must first awaken himself, first open the door of knowledge for himself, not be shackled by rhyme and meter, first study the history, culture, and language of his nation, and only then will he be able to light a fire in the eyes, minds, and souls of his compatriots.

“Oiina”: — To what extent have today’s Tajiks realized the pride and national consciousness that can be drawn from the content of Loik’s poems, and how close are we to achieving these goals?

I. Nazar: — If the modern reader had truly realized that national pride, national consciousness, and the pain of the poet that he wrote about, his thinking would not be what you see in social media discussions, in his writings, and actions.

We still have not recognized the greatness of our Loik.

“Oiina”: — It seems that many poets and literary and cultural figures in our society pretend to follow Loik and praise national values, but in some cases, ignorance of great poems or a superficial understanding of these topics makes this praise empty. How do you evaluate such an approach?

I. Nazar: — Empty pride has long gripped our society. True pride is born from deep knowledge, courage, and then from striving for the future with full baggage.

“Oiina”: — One of Loik’s contributions was that he introduced Tajiks to themselves. This means national self-awareness, so how much have we, as a nation, achieved this self-awareness in the more than twenty years since Loik Sherali’s death?

I. Nazar: — The national self-awareness that is now being so widely proclaimed is mostly about limiting both oneself and others. National self-awareness has a much broader definition than we think.

Look, we start the history of our nation from the Samanids and cut off everything that came before! Didn’t we exist before the Samanids?

We have cut our language off from its powerful trunk and claim that we speak the language of Rudaki, Ferdowsi, Rumi… Loik, Bozor, Gulrukhsor. However, we have acknowledged that this language is not called Persian. We gave it a new name.

We do not recognize its original alphabet. We do not recognize our fellow countrymen and language comrades. We are incapable of tolerating each other’s opinions. How many Fergana, Bukhara, Samarkand, Termez, or a few Khorasan and Iranian people now work in our ministries and universities? Do we have representatives from these cities and lands that we claim in our government? No! We drove them all out, calling them “Uzbeks,” didn’t we?

The “national self-awareness” after the greats Loik, Qanoat, Bozor, and Gulrukhsor has turned into tribal self-limitation, and nothing more.

“Oiina”: — Referring to the words of Sharif Rahimzoda, the former Minister of Economy and former Chairman of the National Bank, one could say that we Tajiks have become too absorbed in poetry and have paid less attention to the exact sciences, which has led to our lagging behind. There are others who support this view. Others believe that literature in general plays a special role in shaping the intellect of a person. Therefore, I would like to know your opinion on the place of literature in the formation of intellect…

I. Nazar: — This debate could go on for years, but what is the point?

Let’s imagine that no one writes poetry anymore—will mathematics, chemistry, physics, astronomy, geometry, and so on develop better because of that?

On the other hand, does Tajik poetry hinder the development of the exact sciences? Is it the poet’s task to create a spacecraft or a bicycle, or to perform the work that a scientist or inventor does?

Of course, a poet can be a mathematician, a doctor, or a driver. We have many poets who are also scholars in the field of medicine.

This is an issue of education and society, which fail to identify talents in various fields and do not strive to develop them.

In my opinion, one cannot call poetry “opium,” like religion, blaming it for our failures and inability to solve problems. Every talent should be supported by the state, whether it is a poet, a mathematician, an artist, or a teacher.

“Oiina”: — Why has social poetry become less prevalent compared to previous years? Or do you have a different opinion?

I. Nazar: — As I mentioned earlier, social poetry is written by a poet who feels all the pains of society as if an earthquake is passing through their heart, who has the courage not to sacrifice poetry for praise, and who does not consider being a singer at celebrations and gatherings to be their main task. Social poetry, which is sometimes called “the poetry of the day,” is not the kind of poetry that, as one might think, has a long life. For example, the ghazal “The Canal Has Come” has lost its original freshness over time, but the ghazal “Ruined Homeland” by the fighter Lohuti will breathe and shout as long as the Homeland is in trouble.

And now, in answering your question, I will pose a question myself: How much social poetry have we written in the last 30 years that we can consider it to have decreased?

“Oiina”: — What is your impression of Loik Sherali and his role in modern Tajik poetry—what did he say, why did he say it, to whom did he say it, and how convincing was it?

I. Nazar: — For a deeper and more accurate understanding of the great Loik, I recommend readers the work of Gulnazar “Loik, as Loik.”

The great teacher Loik always addressed the people, and the poet himself was an embodiment of the people’s spirit. A poet who, in Soviet society, used forbidden words, spoke of a culture and history that were banned and consigned to oblivion. A poet who, in his poetry, in the use of words, in preserving the language, in rubais and couplets, in social and political poetry, did things that his contemporaries could not achieve at the same level.