THE SUPREMASY OF UZBEK AND KYRGYZ OLIVER THE TAJIK LANGUAGE

(Continuation of "The History of a Crude Division")

This essentially nationalist, or more precisely, pan-Turkist idea was promoted by Turkish officers, led by Afandiyev. He was captured as a prisoner of war by Russia and later engaged in educational and training activities in Turkestan. After the establishment of the Soviet People's Republics of Bukhara and Khorezm, he oversaw these matters in both republics.

In the resolution of the Third Viloyat Conference of the Communist Party (b) of Russia on "Autonomy and Strengthening of Turkestan," it was stated: "To unite the laborers and oppressed peoples, communist propaganda should be carried out to eliminate the efforts of Turkic peoples such as Tatars, Kyrgyz, Bashkirs, Uzbeks, and others, and to create small states in the territories of the Soviet Turkestan Republic where it is impossible to unite the Turkic peoples according to their location."

The slogan of Karl Marx, "Workers of the world, unite!" was reinterpreted by the pan-Turkists to fit their goals: the international union of all the oppressed peoples of the world was replaced by a union of Turks, who were united only by their shared past, a common language, and the Islamic religion.

Instead of further developing socialism in Turkestan and involving the local population in the revolutionary transformation, the pan-Turkists sought to restore Pan-Islamism in the form of Pan-Turkism. They implemented an imaginary and brutal "socialist" transformation that was not only against the interests of the Tajiks but also did not benefit the Turkic peoples of Central Asia, such as the Tatars and Bashkirs. This nationalist policy was contrary to the national-cultural interests and autonomy of the nations, particularly the Tajiks, Uzbeks, Kyrgyz, Turkmens, and others. The pan-Turkists exerted historical pressure on the Tatars, Kyrgyz, and Turkmens, and their pursuit of national autonomy was deemed "incorrect" from the perspective of the so-called national unity of the Turkic peoples.

In the field of education, especially in the establishment of schools, the linguistic characteristics of the Uzbek and Turkmen peoples were largely ignored. In such a context, the situation of the Tajik nation, whose existence was denied, was even worse. The Turkification of schools was carried out on the basis of Turkish and Tatar languages. In other words, it was the Turks and Tatars who initiated the reforms in education.

In the Turkestan Republic, even in regions where non-Turkic peoples lived, forced Turkification of schools took place. Moreover, "during the time when Afandiyev was the People's Commissar of Education, this was manifested in the introduction of Turkish exercises, songs, and marches into the curriculum of all schools, the employment of teachers from among former prisoners of war, the ban on introducing new orthography, and the direct promotion of religious propaganda."

At the Third Viloyat Muslim Communist Conference and the Fifth Viloyat Conference of the Communist Party (b) of Russia, a decision was made to recognize the Turkestan Republic as a republic of the Turkic peoples and the Communist Party of Turkestan as the Turkic Communist Party. The proponents of this insane idea sought to turn the backward Turkestan, which was the historical and real homeland of the Tajiks, into a center for the concentration of all Turkic peoples living in the RSFSR. This was not only an attempt to deny the existence of the Tajik people but also a move towards secession from Russia. Another goal was to create a powerful state to oppose the Russians, whom the Turks considered their main enemies. To achieve this, Afandiyev proposed that "foreign policy should be entrusted to the Government of Turkestan."

Recent events and the centrifugal tendencies of Turkic national formations reflect a revival of their separatist aspirations under new conditions and an expansion of pan-Turkism. As historical experience shows, all this took place during revolutionary transformations. Previously, this occurred during the collapse of the Russian Empire, but now it is happening amid the restructuring and democratization of the Soviet empire. The only difference is that pan-Turkist movements, in some cases veiled under Pan-Islamism, have become much more dangerous and aggressive towards non-Turkic peoples.

During the formation of the Turkestan ASSR and throughout its existence, the situation of the Tajiks in this republic did not change. This was especially evident in the appointments and placements of Tajik personnel, the establishment of local Tajik administrative bodies, schools, university faculties, the press, and textbooks.

Prominent Russian and Soviet orientalists and true historians of Central Asia expressed concern about the disregard for the national interests of the Tajik people. Thus, in 1925, V.V. Bartold wrote: "

In 1920, when the Constitution of the Turkestan Republic was approved, only the Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, and Turkmens were recognized as its ‘indigenous peoples,’ while the Tajiks, the ancient inhabitants of the region, were forgotten. The extent of the Tajiks’ protest regarding the national delimitation in 1924 will be shown by the future.”

The entire Soviet system of state and party power, led by local leaders, was influenced by Pan-Turkist ideology. Their efforts to create a “unified Turkic nation,” a “Turkic republic,” a “Turkic Communist Party,” and “Turkic military organizations” are evidence of this. In the struggle against such nationalist views, the Turkestan Commission and the Turkestan Bureau of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) were ineffective. Meanwhile, the forced assimilation of non-Turkic peoples of Central Asia, primarily the Tajiks, was taking place.

At the same time, there was a wealth of international Orientalist literature and numerous sources that confirmed that the Tajiks were and remain the indigenous people of Central Asia. According to these sources, the Tajiks, as the ancient people of Central Asia, managed to preserve and develop their cultural, linguistic, and ethnic characteristics.

Despite the fact that the Tajiks were the second-largest ethnic group in the Turkestan Soviet Socialist Republic, on July 14, 1918, the Central Executive Committee of Turkestan adopted a resolution declaring: “Alongside Russian, the dominant local language (Uzbek and Kyrgyz) is declared the state language.” In a report by the Organizational Commission dated September 14, 1924, it was stated that, given the diverse population of Turkestan, it was necessary to conduct administrative work in three languages (Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Turkmen).

All of this anti-Tajik linguistic policy was implemented contrary to clear historical evidence and common sense. It was no secret that the sweet Tajik language had been, and would continue to be, the language of communication among all the peoples of the East for centuries. The Tajik language was the state language and the language of education in all the states of Central Asia until the national-territorial delimitation. Without knowledge of the Tajik language, it was impossible to study the cultural heritage of the Turkic peoples. Yet, representatives of these peoples refused to acknowledge this fact.

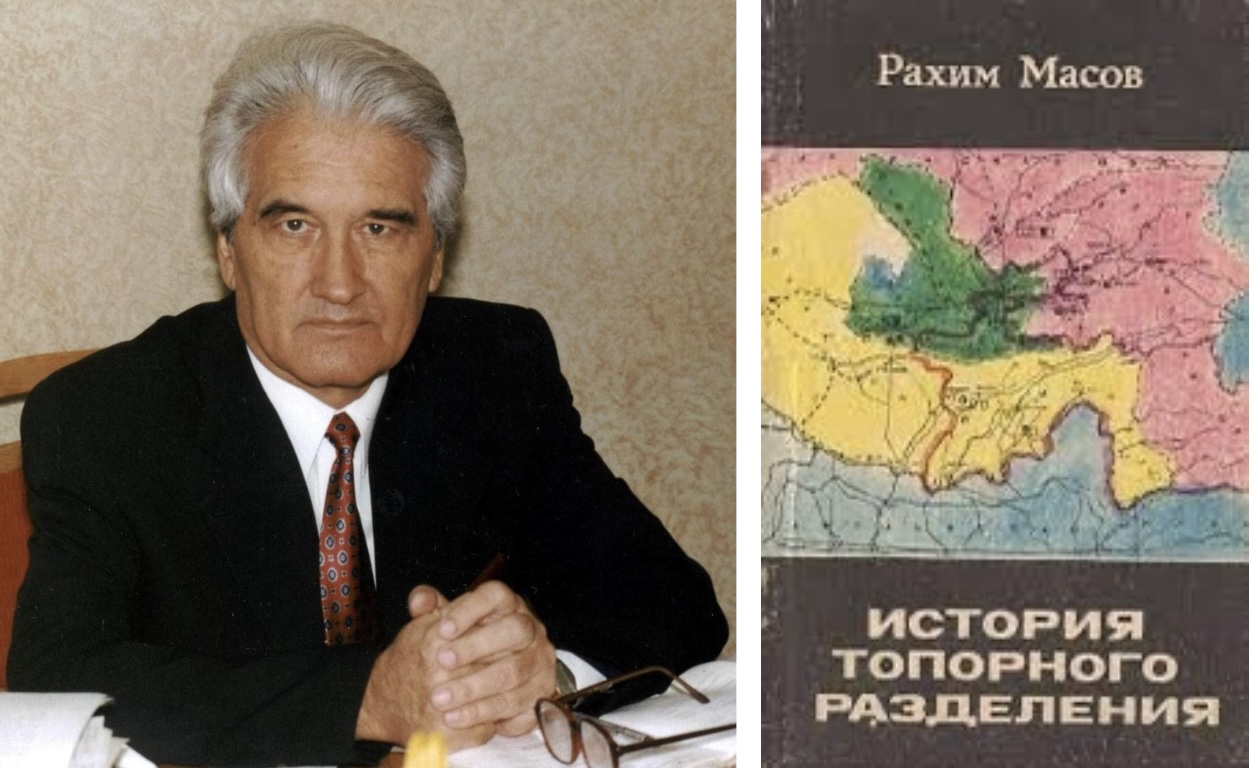

Rahim Masov